The sun may face ‘rare but extreme’ events that could impact life on Earth

Superflares are now a new element on the list of natural disasters to be concerned about.

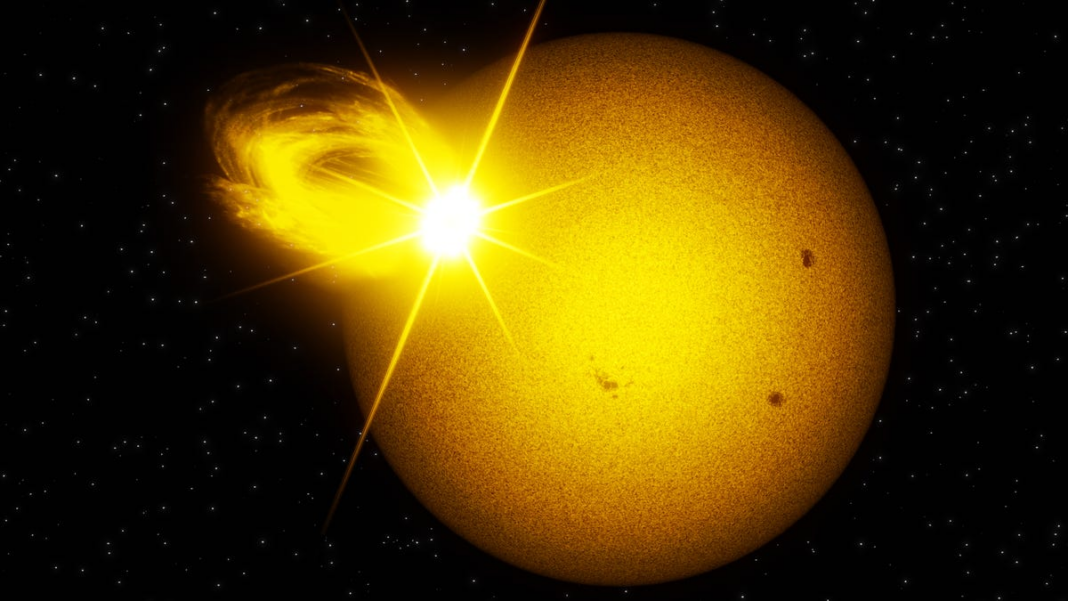

These superflares are exceptionally powerful solar flares, releasing energy up to ten thousand times greater than that of regular solar flares.

Why is this concerning? A recent study of 56,000 stars similar to the sun indicates that such stars may experience massive superflares roughly once every century. This suggests that our sun could also produce these extreme solar emissions at a comparable frequency, as stated by the American Association for the Advancement of Science, which released the study.

If our sun were to unleash a superflare, it could severely damage our communication satellites and disrupt the power grid on Earth.

Valeriy Vasilyev, the lead author of the study from the Max Planck Institute for Solar System Research in Germany, expressed surprise at how common superflares seem to be for sun-like stars, given that previous research suggested such events could occur only once every thousand or even ten thousand years.

What is a solar flare? What is a superflare?

Solar flares are sudden, intense bursts of electromagnetic energy from the sun, releasing significant energy in short bursts. These can affect the upper atmosphere of Earth and occasionally result in communication outages.

In contrast, superflares are infrequent, high-energy explosions significantly stronger than the largest solar flares recorded on the sun. Superflares can release over one octillion joules of energy in a brief moment and manifest as sharp brightness spikes in distant stars.

“We cannot observe the sun for thousands of years,” Sami Solanki, director at the Max Planck Institute and coauthor of the study, explained the research concept. “However, we can study the behavior of thousands of stars similar to the sun over shorter durations, which allows us to estimate how often superflares occur,” he said.

What happens if a superflare strikes Earth?

If a solar superflare were to hit Earth, the first impact would be a powerful surge of X-ray and ultraviolet radiation, based on a 2019 study published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

The study notes, “This would disturb the ionosphere, disrupting satellite navigation signals essential for critical services and infrastructure.” Additionally, this radiation would heat the upper layers of the Earth’s atmosphere, causing them to expand, increasing drag on satellites, potentially resulting in some being lost.

Following this, a surge of high-energy protons, propelled by shockwaves from the sun’s atmosphere, would impact Earth. This could further damage satellites and jeopardize global communication systems. “These high-energy particles can irreparably damage processors,” said astrophysicist Karel Schrijver from Lockheed Martin in the 2019 study.

In the worst-case scenario, if a massive coronal mass ejection aligns directly with Earth, it might trigger a severe geomagnetic storm, creating electric currents potent enough to disrupt power grids. A notable example is the nine-hour blackout in Quebec caused by a lesser coronal mass ejection in March 1989.

When might a superflare happen?

The new study does not specify when the sun might unleash a superflare. However, it does emphasize the need for caution.

“The latest findings are a clear reminder that even the most extreme solar events are inherent to the sun’s natural behavior,” said Natalie Krivova, a coauthor of the study from the Max Planck Institute.

During the notorious Carrington event of 1859, one of the most intense solar storms in the past two centuries, the telegraph systems across significant areas of northern Europe and North America were disrupted.

Estimates suggest that the flare linked to this event emitted merely one-hundredth of the energy of a superflare. Nowadays, not only is the infrastructure on Earth a concern, but satellites are also particularly vulnerable, according to the new study. Satellites play crucial roles in services such as television, phone communications, GPS, credit card transactions, and weather monitoring.

This study was published on Thursday in the peer-reviewed journal Science, a publication from the American Association for the Advancement of Science.