Can you read cursive? It’s a special skill the National Archives needs.

The National Archives seeks volunteers with a rare talent: Reading cursive handwriting.

If you can read cursive, the National Archives is interested in talking to you.

There are over 200 years’ worth of U.S. documents that need to be transcribed or categorized, and most of these documents are handwritten in cursive. This means they need individuals who can read this elegant and flowing script.

“Being able to read cursive is like having a superpower,” Suzanne Issacs, a community manager at the National Archives Catalog in Washington D.C., stated.

Issacs is part of a team that oversees over 5,000 Citizen Archivists working to read and transcribe more than 300 million digitized items in the Archives’ collection. They are currently seeking volunteers with this increasingly uncommon skill.

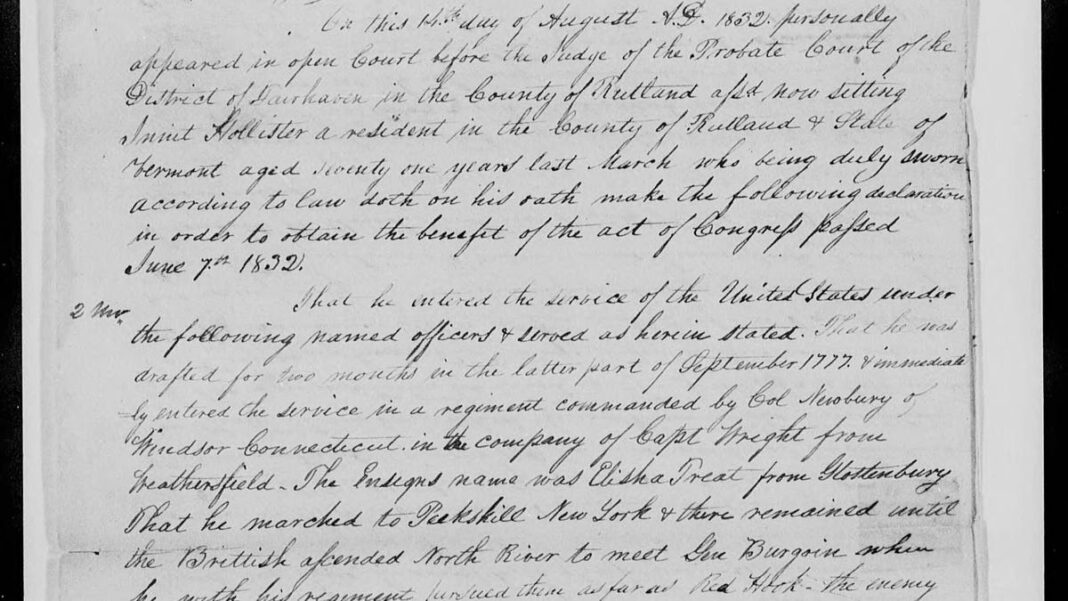

The documents include a variety of historical records, from Revolutionary War pension applications to Charles Mason’s field notes of the Mason-Dixon Line, along with immigration papers from the 1890s and Japanese evacuation records from World War II to the 1950 Census.

“We create assignments for volunteers to help transcribe or categorize records in our collection,” Issacs explained.

To volunteer, you simply need to register online and get started. “There’s no application process,” she noted. “You just select a record that hasn’t been transcribed yet and follow the instructions. It’s easily manageable for just a half-hour each day or week.”

Having the ability to read cursive is extremely beneficial since many documents are written in this style.

“It’s not just about whether you learned cursive in school; it’s also about how frequently you use it today,” she added.

Cursive is Declining in Popularity

Americans have been losing their ability to read this connected writing style over the decades.

In the past, elementary students were taught beautiful copperplate writing, and penmanship was often part of their grades.

This began to change when typewriters became commonplace in offices in the 1890s, with further decline following the rise of computers in the 1980s.

Even so, handwriting was still deemed a vital skill until the 1990s, when communication shifted towards emails and later texting in the 2000s.

By 2010, Common Core standards prioritized typing skills and no longer mandated handwriting instruction, assuming that most student writing would occur on computers.

This led to a backlash, and as of 2023, at least 14 states require cursive handwriting instruction, including California. However, this doesn’t necessarily translate to actual usage.

Historically, most American students began cursive writing instruction in third grade, making it a significant milestone, according to Jaime Cantrell, an English professor at Texas A&M University, Texarkana, whose students actively participate in the Citizen Archivist initiative, applying their skills in reading historical documents.

For Cantrell’s generation, “cursive was a rite of passage into literacy during the 1980s. Once we learned it, we could write like the adults,” she remarked.

Although many of her students today were taught cursive in school, they rarely use it and seldom read it. She notices this because she writes her feedback on their assignments in cursive.

Some students aren’t even typing anymore; they often use speech-to-text technology or even AI. “I know this because their submissions lack punctuation,” she observed.

It feels like a flowing thought process.

Gaining confidence in reading and writing cursive can be a challenging journey, but it’s not impossible. Mastering this skill opens the door to a myriad of historical documents.

Cursive remains an important skill

In 2023, California enacted legislation mandating the teaching of “cursive or joined italics” for students from grades one to six. The purpose, as explained by the law’s author, is to enable students to interpret primary source historical materials.

This approach aligns with how students in Cantrell’s class utilize cursive. One of her courses focuses on interpreting documents from the 18th and 19th centuries, and a special project involves participating in the National Archives’ transcription initiatives.

“There is definitely a learning curve,” Cantrell acknowledged. “But my students are persistent. They believe in their mission and feel they are making a significant contribution.”

According to Nancy Sullivan from the National Archives, learning to read cursive is just the first step in interpreting older texts. The handwriting from the 18th and 19th centuries differs greatly from what is taught in today’s third-grade classrooms.

Interestingly, Cantrell notes that some of the oldest writings can be the easiest to understand.

“When you examine the letters from Abigail Adams to her husband, President John Adams, and his replies, the cursive style is truly artistic and remarkably consistent,” she stated.

AI has its limits with cursive

While artificial intelligence is beginning to decipher cursive writing, it still requires human assistance, according to Sullivan from the National Archives.

The Archives collaborates with FamilySearch, a non-profit organization associated with the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, which provides free genealogical tools and access to historical records.

FamilySearch has created an AI program designed to interpret handwritten documents, but an individual is needed for the final review.

“Mistakes are common,” she explained. “That’s why we refer to it as ‘extracted text,’ and our volunteers must compare it to the original document.” Only after a volunteer reviews the text is it designated as an official transcription.

Furthermore, said Issacs, AI can struggle with the frequently challenging documents that volunteers encounter. These documents may be damaged, smudged, creased, or marked up. For instance, Revolutionary War pension applications required widows to validate their marriages, often including handwritten family trees that were clipped from their family Bibles.

Poor handwriting can also be a barrier. “Some Justices of the Peace had horrendous penmanship,” noted volunteer Christine Ritter, 70, from Fairless Hills, Pennsylvania.

Volunteers face challenges like crossings out, content written on the reverse side that bleeds through, peculiar and invented spellings, archaic letter forms (where a double ‘S’ might appear like an ‘F’), and even children’s doodles. Additionally, many obsolete legal terms can puzzle even the most knowledgeable readers.

“It’s like piecing together a puzzle. I find it very enjoyable,” shared volunteer Tiffany Meeks, 37. After starting her transcription volunteer work in June, she learned a new term: paleography, which refers to the study of historical handwriting.

“It felt like I was mastering a new language. I was not only refreshing my cursive skills but also diving into old English,” she elaborated. “Paleography is the term I learned for interpreting ancient documents.”

No cursive skills? No worries!

Issacs from the Archives emphasizes that volunteers don’t need to have prior cursive knowledge to start; they can learn along the way. “Having that skill is beneficial, but it’s not a requirement.”

For example, there’s a “no cursive needed” option available for reading Revolutionary War pension records. Instead of transcribing these records, volunteers can assist by adding “tags” to existing transcriptions done by other Citizen Archivists. This makes the records easier to search.

You can also learn as you contribute, said Ritter.

“When they first assigned me a document, I panicked, thinking, ‘I can’t read this!’ But the more I do it, the simpler it becomes,” she reflected.

Ritter is currently working on pension files for soldiers who fought at the Battle of Guildford Courthouse on March 15, 1781. As she works, she thinks about how meaningful it will be for families to uncover such historical items about their ancestors.

Although she once took pride in her impeccable handwriting, she now describes it as “terrible.” Yet, she excels at reading cursive, a hobby that she cherishes.

“I start my day with breakfast alongside my husband; then he heads off to fish while I retreat to my workspace. I set up my computer, tune into my favorite oldies station, and begin transcribing. I truly love it,” she remarked.