In ‘Leonardo da Vinci,’ Ken Burns reveals the man behind the myth as a seeker of knowledge

Ken Burns and his team are known for tackling large subjects such as The Civil War, National Parks, Baseball, and Country music.

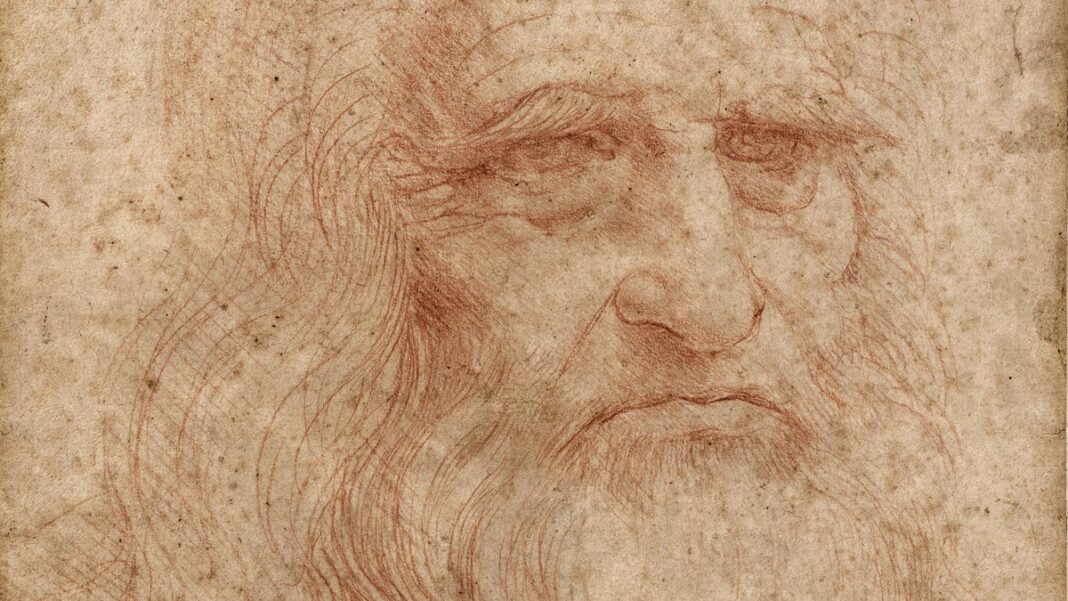

However, they sometimes delve into the lives of individual historical figures, like Thomas Jefferson and Muhammad Ali. In his newest documentary, Burns focuses on the legendary Leonardo da Vinci, not the actor DiCaprio, but the Renaissance genius from Vinci, Italy. This four-hour presentation, titled “Leonardo da Vinci,” will air on PBS on November 18 and 19 (check local listings).

“Leonardo represents a topic that is even broader than some of our previous works,” says Burns, who directed the film with his daughter Sarah Burns and son-in-law David McMahon. “His insatiable curiosity makes him the perfect subject because of this vast knowledge and deep understanding of humanity in relation to the universe. There’s nothing bigger than that.”

Leonardo’s interests spanned across various fields, including painting, engineering, and natural sciences. As a result, the documentary features insights from experts in art, medicine, theater, aviation, and filmmaking. Additionally, it candidly discusses Leonardo’s personal life, including his homosexuality and his strong relationships.

“Every one of our projects is a journey of discovery,” says Sarah Burns, who spent time in Florence to deepen her understanding of the iconic city and its most famous resident. “We often choose topics precisely because they are unfamiliar to us. However, with someone like Leonardo, the learning curve was particularly steep.”

The Burnses recently shared some fascinating insights about Leonardo with YSL News.

Question: Leonardo has been the subject of countless biographies, including a recent one by your expert Walter Isaacson. What new insights did you gain about him?

Ken Burns: Everything I learned was new to me. For instance, I knew about his artworks, but I was surprised to find that he created fewer than 20 paintings, and only half of them were finished. More importantly, I discovered the intricacy of his painting techniques that brought forth what he referred to as the “intentions of the mind” of his subjects, which made him stand out among artists. It’s remarkable that although Leonardo is the oldest individual we’ve studied, he still feels incredibly relevant today. If he were alive now, he’d be impressed to know we’ve landed on the moon.

Sarah Burns: I was fascinated by his personality. It’s common to think of him as a solitary, tortured artist, but that’s far from the truth. People enjoyed his company; he loved music and was quite flamboyant in his attire. We aim to portray him as a genuine, multi-faceted individual, not as some mythical figure with prophetic capabilities but as a man with friendships and connections.

It’s astounding to remember that his contemporaries included Michelangelo and Raphael. What fierce competition!

Ken Burns: Definitely. At the moment, I’m focused on my next documentary about the American Revolution, and it’s similar in that sense with figures like Washington, Jefferson, Hamilton, Adams, and Monroe—true giants. You really have to ask yourself how all that happened. With Leonardo, it feels even more extraordinary.

Sarah Burns: These artists thrived in an extraordinary era. Cities like Florence and Milan in the Renaissance provided them with the freedom to innovate, thanks to humanism and wealthy patrons. There was a compelling dynamic of mutual ambition and competition among them.

Despite the brilliance of figures like Michelangelo, your film positions Leonardo as truly extraordinary.

Ken Burns: Absolutely, Leonardo is in a league of his own. Just consider the intricate details in “The Last Supper,” which looks more like a dramatic film than a mere painting. While Michelangelo was brilliant, he didn’t explore topics like water dynamics or the mechanics of flight, nor did he foresee advancements in cardiac surgery like Leonardo. In the gradual evolution of humanity, suddenly someone like him emerges. If we typically use 10% of our brain capacity, he’s using 75% or possibly 110%. Everyone will take away something different from the film, but I hope it inspires at least a few viewers to aspire to be a bit more like Leonardo.

So, are you suggesting we should cultivate a sense of curiosity about everything around us?

Sarah Burns: Precisely. Leonardo is inherently inquisitive and has an almost obsessive drive to learn. He delves deeper into every subject, asserting, “I want to grasp how the human body functions not just for painting, but I will also dissect corpses to expand my understanding of the body.” This relentless curiosity distinguishes him even from his highly driven contemporaries.

Leonardo’s experience as an illegitimate child made him an outsider, a fact that influenced his later life significantly.

Ken Burns: This is crucial because being born out of wedlock at that time barred him from attending university. Consequently, he avoided the elitism of academic environments. He comes to believe that “nature is my greatest teacher, and it is flawless.”

Sarah Burns: He challenges everything around him, carrying almost a defiant attitude towards it.

Obtaining permission to film “The Last Supper” took you 18 months, whereas you were welcomed to film “The Mona Lisa” at the Louvre almost effortlessly. Why does “The Mona Lisa” only make an appearance in the film’s concluding moments?

Sarah Burns: Our intention was to place it within the larger narrative of Leonardo’s life. Even though he began it 15 years before his passing, he infused that painting with insights and knowledge accumulated throughout his life: his anatomy lessons, observations of nature, and understanding of the body’s connection to the earth.

Ken Burns: Shot in such a close manner, one can truly appreciate his remarkable technique. There are no obvious lines; everything blends seamlessly, transitioning from her cheek to her nostril to her forehead, each layer further crafted with paint. As one of our art experts comments in the film, the way he subtly captures the pulse of blood beneath the skin makes this artwork come alive. It’s as if he has transformed into a deity of painting.