Are students checking Trump’s claims on voting? Here’s what they’re learning.

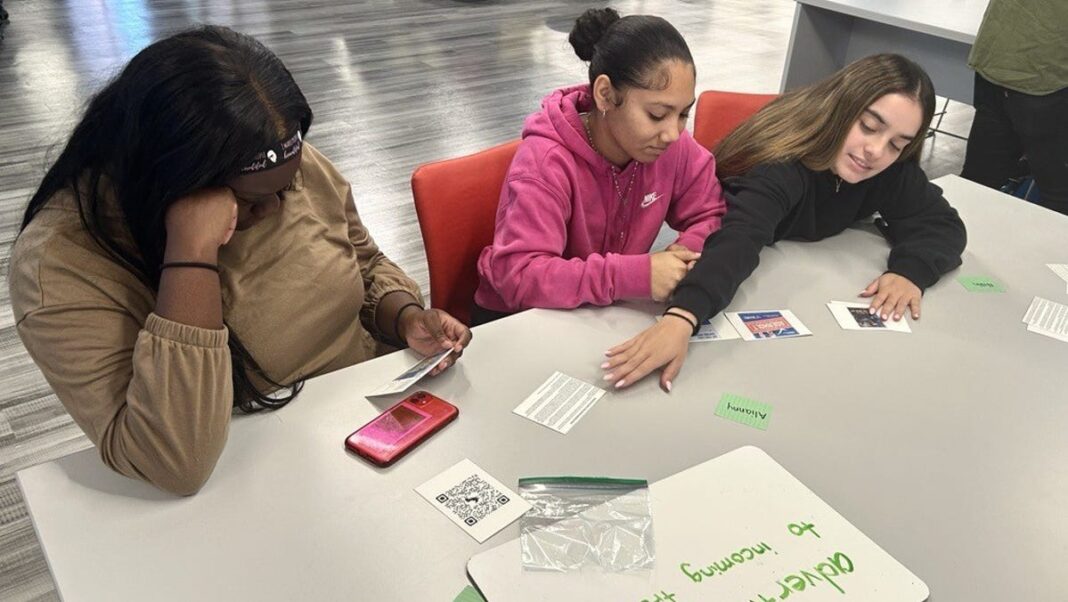

BALDWIN, New York – On a crisp fall morning, just weeks before the 2024 presidential election, Jayla Rennocks and her classmates were discussing a social media image of Donald Trump that included the phrase “I’m voting Aderholt for Congress.” They were trying to decide if this post represented propaganda, publicity, or news.

The purpose of their high school social studies class was to determine if pieces of information aimed to influence their voting choices, sell a product, or provide news updates, explained their teacher, Tayla Plotke.

This advertisement is “designed to motivate you guys to take action,” she informed the class.

For Plotke, a history enthusiast with seven years of experience in the district, it’s vital for students to learn how to judge whether the information they encounter online is truthful or has hidden agendas. She is part of a movement of educators encouraging students to critically evaluate their news sources and to develop skills to assess the reliability of the information they find.

Many K-12 schools across the country have started to emphasize news literacy among young individuals. This year, they are particularly focusing on the surge of misinformation online about the 2024 presidential election, the Israel-Hamas conflict, and other significant topics for voters and democratic processes.

Baldwin School District is one of many nationwide that stipulates students must acquire news literacy skills prior to graduating high school. These skills encompass identifying biases in news articles, discerning between advertisements and news pieces, and spotting misinformation generated by artificial intelligence.

In discussions with YSL News, district officials, educators, students, and advocates for news literacy emphasized the importance of young people being able to distinguish between credible news and misinformation. Recently, some state lawmakers have made news literacy courses a graduation requirement.

Nonetheless, there has been significant opposition from individuals worried about the political implications and the overall value of mandating a news literacy course, as noted by Chuck Salter, CEO of The News Literacy Project, a nonpartisan organization that offers resources to educators. Others express concern about the burden of integrating this curriculum alongside other mandated coursework.

Since the 2018-2019 academic year, the Baldwin Union Free School District in Long Island has required high school students to learn news literacy. Superintendent Shari Camhi believes this approach is beneficial for a generation that is heavily engaged with information and news.

“All you have to do is log into any social media site. Even verifying the author of a piece requires diligence,” she stated. “In my time, we used the World Book Encyclopedias,” she recalled, explaining that unlike encyclopedias, information online may not be “fact-checked and thoroughly verified.”

‘The educational system must act swiftly’

Howard Schneider from Stony Brook University, who instructs news literacy to college students, played a role in training educators at Baldwin High School.

When Schneider began teaching college students about news literacy in the 2006-2007 school year, the United States was just beginning to experience a social media transformation, as platforms like Facebook, Twitter, and YouTube became prominent sources of information between the presidencies of George W. Bush and Barack Obama.

“We were at a pivotal moment, witnessing the impending challenges,” Schneider stated. “However, the broader society was still lagging in addressing these issues.”

Given the flood of misinformation and the prevalence of AI-generated content, schools have an obligation to “respond without delay,” he remarked.

“We are amidst the most significant communication shift in 500 years – since Johannes Gutenberg,” he added, referring to the inventor of the printing press. “It’s akin to placing ten-year-olds behind the wheel of a car without a driver’s license.”

A key lesson in his news literacy curriculum includes what he refers to as lateral reading, which encourages students to “often step outside the original text” and find additional sources to verify the authenticity of the information they are consuming.

“Students can no longer engage with content in the same manner while watching videos, navigating social media, or reading text,” Schneider explained.

Schneider referenced a 2022 study from Stanford University’s Graduate School of Education indicating that nearly 500 students from six high schools, after participating in six 50-minute lessons on lateral reading techniques, were better equipped to “assess the credibility of digital content” compared to those who had not received similar instruction.

How are students learning to counter misinformation?

Three states – Connecticut, Illinois, and New Jersey – mandate that schools provide news literacy instruction to students.

California, Colorado, Delaware, Ohio, and Texas have enacted laws requiring states to implement news literacy standards, although these laws do not specifically mandate teaching the skills, according to a state tracker from the News Literacy Project.

The access to news literacy classes differs by district and school across various states, according to Salter from the News Literacy Project. In certain areas, these classes aren’t offered at all.

The curriculum is often delivered by enthusiastic teachers or guided by district authorities, as noted by Salter.

In Las Vegas, Erik Van Houten, who works as an assistant principal and high school history teacher, and Erin Wilder, a high school educator in Gwinnett County, Georgia, are utilizing the organization’s resources to instruct students in news literacy.

Van Houten applied for financial aid after observing that students in his senior class were spreading incorrect information regarding the Israel-Hamas conflict online. His school was selected to receive educational resources.

Last year, Van Houten convened the history teachers at his school to create a strategy for teaching students about the broader Israel-Palestine situation, aiming to help them identify misleading news about the conflict.

“From start to finish, I noticed a significant improvement in their understanding of the topic,” he shared. “Even middle school teachers reported having deeper discussions about the issue with their students.”

This academic year, his students are concentrating on analyzing news related to the upcoming 2024 presidential election.

For Van Houten, enabling students to identify and combat misinformation related to elections is crucial, particularly because some of them will be voting for the first time and reside in a swing state. He wants to ensure they have accurate information before making their voting decisions.

In Georgia, Wilder recently conducted a lesson highlighting the significance of lateral reading.

She presented them with an article covering a workers’ strike against Boeing and encouraged her students to think critically about it.

Wilder instructed them to evaluate the article’s credibility, assess any potential biases in the sources, and consult other articles before forming a conclusion. She emphasizes to her students that no source is “inherently right or wrong,” but examining multiple perspectives allows for a more comprehensive understanding of various issues.

At the conclusion of the semester, Plotke in Long Island will task her students with fact-checking news articles created by artificial intelligence to ensure they do not fall for misinformation in this age of widespread AI-generated content.

“It’s unavoidable—it shows up on Google AI. The students are engaging with it,” she remarked.

‘Empowering students with knowledge’

The News Literacy Project advocates for more states to establish laws requiring students to learn a news literacy curriculum, as noted by Salter.

Next, the nonprofit will collaborate with the Los Angeles Unified School District (LAUSD), which is the second largest district in the United States. Educators in Los Angeles are being trained in techniques to help students identify and combat misinformation. LAUSD plans to integrate media literacy across its elementary and secondary schools, as confirmed by Shannon Haber, a spokesperson for the district in an email to YSL News.

“This resource enhances the development of critical thinking skills and equips students with the knowledge and tools necessary to assess a source’s credibility and discern fact from falsehood,” Haber stated.

Schneider from Stony Brook University mentioned that elementary educators are now teaching students how to distinguish misinformation, and in some Long Island districts, news literacy content is being translated into Spanish for Spanish-speaking students.

‘Questioning what they see‘

Back in Long Island, the lessons have already enabled students like Rennocks, age 18, and her classmates to critically evaluate the credibility of the information they encounter online.

While seated with her peers, Rennocks expressed her distrust of news outlets as unbiased sources of political information, and the others concurred.

They indicated a preference for television debates over news articles, finding it more trustworthy for candidates to speak directly rather than filtering through potentially biased reports on social media.

Rennocks shared that she recently saw a post on X from Cardi B, where the rapper criticized a statement made by Donald Trump. Instinctively, she turned to Google to fact-check the claim. The skills acquired in class led her to validate her skepticism.

Upon checking other sources, she was surprised to discover that Cardi B’s assertion was correct.

Trump had indeed stated, “Christians, get out and vote, just this time. You won’t have to do it anymore. You got to get out and vote. In four years, you don’t have to vote again,” to a group of conservative Christians in West Palm Beach, Florida.

Rennocks initially doubted that the former president would make such a statement.

“That made me want to look it up,” she remarked. “I was like, ‘What did he just say?'”

Other classmates mentioned they also viewed the same video and cross-verified it with different sources. They frequently express skepticism towards mainstream media, opting to cross-check information from various outlets.

However, Rennocks voiced her concerns that many of her peers—those outside her social studies class—might not demonstrate the same critical approach.

Many individuals rely on a single news source, trust what their favorite celebrities or influencers share on social media, or use AI for their information, she pointed out.

“Our generation is truly fixated on social media and tends to believe everything they encounter,” she concluded.