Have you heard of the Rosenwald Schools created for rural Black students a century ago?

In a secluded wooded area in Lockhart, Texas, a building stands out.

On the side facing East Market Street, six windows elegantly frame a simple entrance. A walk around the two-story structure showcases its resilience through various public functions and a lengthy period of neglect.

This building is one of the Rosenwald Schools.

Constructed in 1923, it was dedicated to providing education for segregated Black students in the region, along with their six teachers.

My first encounter with the abandoned school was in 2016 when I was researching historical Lockhart. I realized then that I had never noticed any of the 527 Rosenwald campuses that were built throughout rural Texas under the Julius Rosenwald School Building Program.

Across the South, a staggering 4,978 of these schools were built during the early 20th century, funded by matching grants from a program established in 1917 by Julius Rosenwald, a Jewish businessman and part-owner of Sears, Roebuck & Company, the largest U.S. retailer at that time.

Rosenwald initiated this fund following the advice of educator and civic leader Booker T. Washington, who promoted self-reliance and vocational education for African Americans.

Many of these schools were established on land owned by local communities, using local resources and labor, primarily in freedom colonies of self-sufficient African Americans who still had fresh memories of slavery.

I’m taking a wild guess that many readers — like I was in 2016 — might not have heard of Rosenwald Schools or the movement behind them. If you’re interested, check out “A Better Life for Their Children,” a stunning photographic exhibit at the Bullock Texas State History Museum, available until February 23.

Then, keep your eyes peeled. These schools can be found throughout East Texas, although some have vanished, others lie abandoned, and many have been repurposed into community spaces like churches, museums, or centers.

What can visitors expect at the history museum?

As soon as visitors step into the spacious first-floor gallery dedicated to temporary historical exhibitions, they are struck by the open layout. This gallery is often filled with items. However, “A Better Life for Their Children” features primarily large black-and-white photographs by Andrew Feiler from locations throughout the South, which were first showcased in Atlanta.

To connect the images to the local context, curators at Bullock have included historical artifacts such as desks, teacher’s chairs, a pot-belly stove, lunch trays, and typewriters previously used in Texas Rosenwald Schools.

Additionally, the Bullock has created a large, informative map illustrating the locations of these schools throughout Texas.

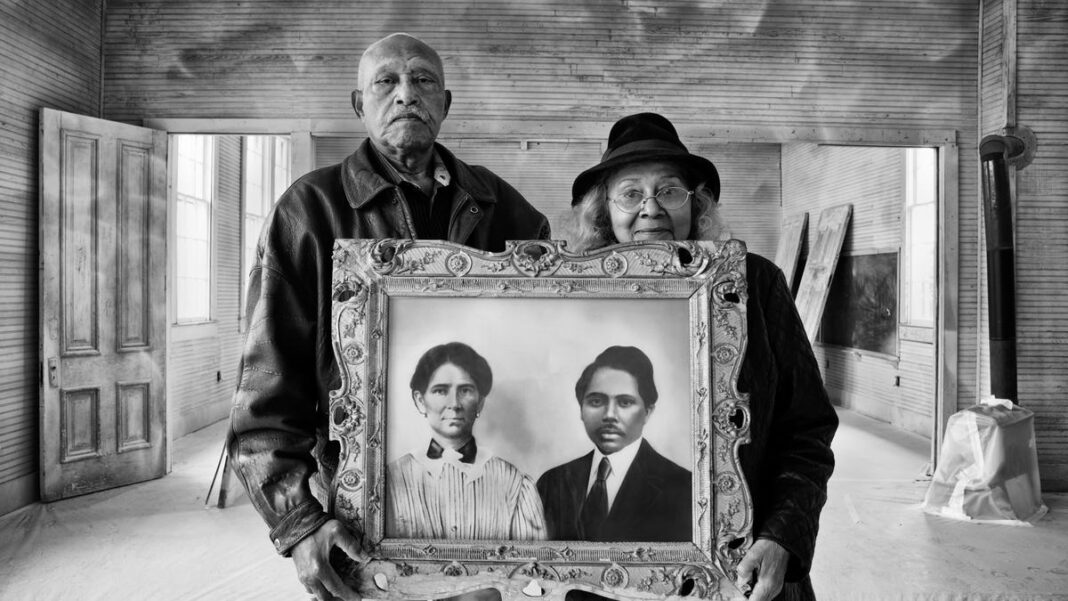

To the left of the entrance, visitors will find a striking photograph of Elroy and Sophia Williams captured by Feiler at the Hopewell School in Cedar Creek, Bastrop County. The couple is seen holding a portrait of Sophia’s grandparents, Sophia Veal and Martin McDonald, former slaves who donated the land on which the school was built.

The Hopewell School was one of five Rosenwald Schools established in Bastrop County.

Established in 1922, the Cedar Creek school operated until the 1950s,” the wall text indicates. “As former students, teachers, and their descendants recognized the building’s historical importance, they mobilized the community to protect it. Restoration began in 2016, and the building now functions as a community center.”

Also on display is the original portrait of Veal and McDonald from the 1920s.

“After the end of slavery, Martin McDonald farmed and raised animals, eventually saving enough to purchase land,” explains a wall text. “Following his passing, his wife, Sophia Veal, donated land for the Hopewell School’s construction in 1919. Although Martin never had the chance to attend school, his donation opened educational doors for family and neighbors. Their daughter, Artelia McDonald Brown, became the school’s first teacher, while her daughter, Sophia Williams, was a student there.”

This narrative — both specific and broadly relatable — is a common theme throughout the exhibit. It demonstrates that, a century ago, Black parents, whose children were barred from the white school system, were determined to secure a bright future for their kids. With external support, they built that future with their own resources.

One striking photograph that exemplifies the era showcases the students and teachers at Jefferson Jacob School (1917–1957) in Jefferson County, Kentucky, standing orderly on the school’s steps.

“In the 1920s, two teachers and 55 students were photographed outside the Jefferson Jacob School,” according to a wall text. “During the early stages of the school building initiative, Booker T. Washington shared photographs like these of proud schoolchildren and teachers with Julius Rosenwald. Deeply inspired by these images, Rosenwald decided to broaden his efforts.”

What led to the creation of these schools?

Julius Rosenwald, the son of Jewish immigrants, played a pivotal role in turning Sears, Roebuck & Company into the largest retailer globally. Booker T. Washington, who was born into slavery, founded Tuskegee Institute, now known as Tuskegee University, in Alabama.

In 1911, Rosenwald and Washington met. At that time, most Black public schools in the Southern United States were housed in makeshift buildings made from poor-quality materials and were funded by a fraction of what was allocated for white children’s education. Many regions lacked public schools for Black students altogether. To combat this, Rosenwald generously donated millions to establish new schools.

“Rosenwald and Washington formed one of the first collaborations between Jews and African Americans to address educational disparities innovatively, leading to the program known as the Rosenwald schools,” states the exhibit’s introductory text. “Between 1912 and 1932, this initiative resulted in the construction of 4,977 schools for African American children across 15 Southern and border states, with one more added in 1937. This program significantly improved educational attainment for African Americans and nurtured the leaders and advocates of the civil rights movement.”

What is the background of this exhibit?

Of the 4,978 original Rosenwald schools, roughly 500 still stand today.

To document this story, photographer Andrew Feiler traveled over 25,000 miles, capturing images of 105 schools and interviewing many former students, teachers, preservationists, and community leaders across all 15 states involved in the initiative.

This is not Feiler’s first extensive project on cultural history. His work has been featured in prominent publications such as Smithsonian, Architect, and Preservation magazines, as well as on CBS This Morning, PBS, and NPR. His photographs are showcased in galleries and museums, including the National Civil Rights Museum in Memphis, the National Center for Civil and Human Rights in Atlanta, and the International Civil Rights Center & Museum in Greensboro, North Carolina.

“Andrew Feiler is a photographer and author, and is also a fifth-generation Georgian,” states a wall text. “Growing up Jewish in Savannah, he has been influenced by the rich diversity of the American South. Feiler is actively involved in community initiatives, serving on various nonprofit boards, and advising numerous elected officials and candidates. His art reflects his civic engagement.”